Country house

I have told you about the love I have for this house before.

The house stands at the end of the village, which overlooks an apple orchard. This is not far from the Adriatic. There are just nine houses in the village, along with a church and a creek. The house was built two centuries ago, although nobody knows when exactly. The last date chiseled in the face of the stone portal is 1806.

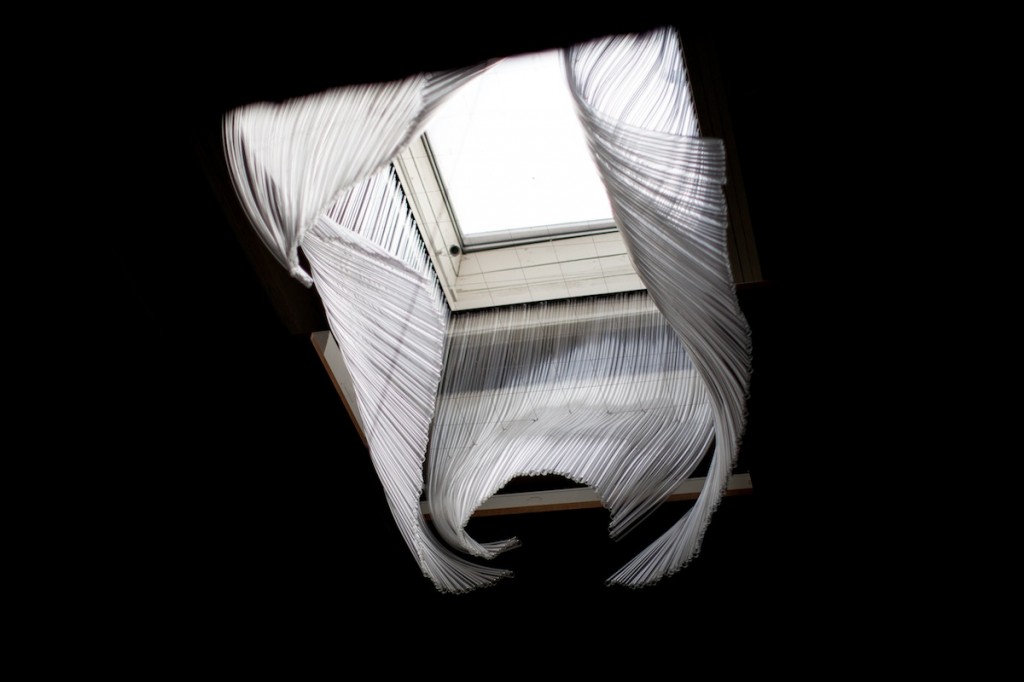

The walls are a yard thick in places, meant to hold warmth in winter and cool in summer. The stone is held together by crumbling mortar. The enormous and very old oak wine barrels confirm stories of once existing “ostaria”. The front double door opens into a vast courtyard, surrounded by living quarters, a barn and a wine cellar. The back of the house is built into a hill, a drain runs under the floor. The roof tiles are terra cotta, underneath all whitened with the natural pigment of the lime stone dust, exposing the terra cotta in the geometric pattern. The timbers are worm-riddled.

The previous owners included four cousins; one of them, Nino Capone, is a cousin of Al Capone. before emigrating to New York, the Capones lived in the nearby town of Fiume. Nino’s mother, as a little girl growing up in the house, moved as a young woman to Trieste, where she met Al Capone’s uncle, married him and they had a son Nino, who become a partial owner of the property upon his mother death.

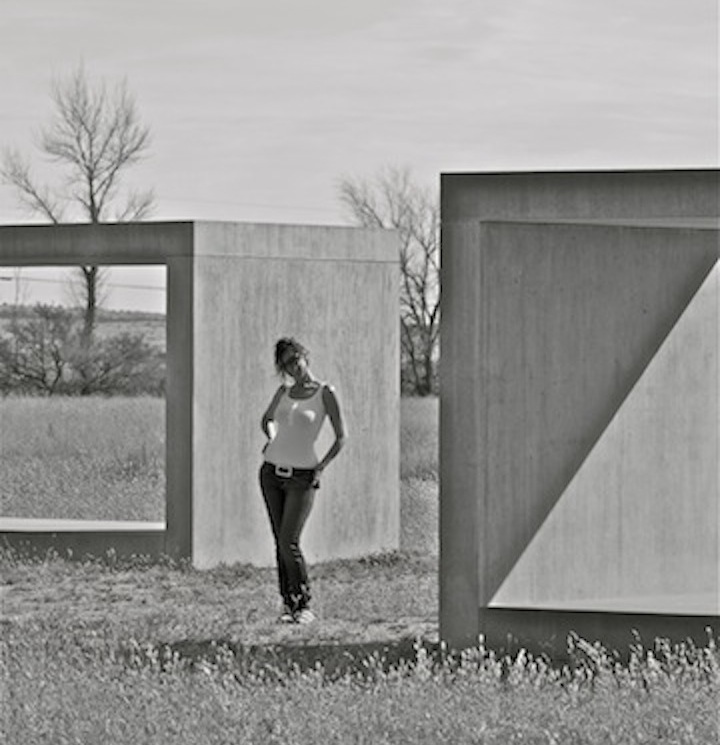

Adriana, my daughter, and I spend almost every summer there, but I think of the house much more often, dreaming about it the way you would dream of a lover. I visit it the way you would a vacation home a few hours away. In my visions I am often in the courtyard, sitting under the wine pergola, sipping the local wine, feeling the sun.

Or, I remember the times that this or that happened, the time Adriana found a monstrous spider on the wall and carefully took it to the orchard or the time we watched a ferocious fight between a scorpion and centipede. Or, memories of our neighbor Maria, now gone, who had this beautiful tradition of leaving the basket of her garden treasures: tomatoes, cucumbers, onions, or whatever was ready to harvest that day, leaving it for me to find every morning when I opened the frontdoor.

When I am really there, I am always busy, cleaning the wine cellar, tending the orchard, oiling the timbers, pruning the vines. It’s not just the upkeep, it’s a very intimate work I do with my own hands. It’s a relationship, with the stone walls, with the village, with its history and mine.